When, and why, did you decide to start painting?

It was during our first (or second?) trip to the American south-west, in 1997. On our way to see the Mossets, we bought a map of Tucson. It was interesting both pictorially and in terms of its content. Tucson’s the second largest city in Arizona, and though its centre’s quite dense, its outskirts, on the edge of the desert, are in a state of ongoing emergence. Poring over the map, we realised that as you move away from the city centre the information becomes more and more sparse — non-existent, in fact. And it was this ability to reproduce an absence of information that surprised us most — shocked us, in a sense. The pages of that map, with their patches of colour that indicated districts or postal codes, immediately spoke to us of painting.

Back in Paris, we firstly thought about photographing them, and then reproducing them on a large scale using a digital printing system. But we quickly decided that this wouldn’t do. At the time we were working with language, and operating in different media: neon, photographs, light projections. We thought of ourselves as being in the margins of language, involved in the structuring of the text — our attention was increasingly turning towards intervals and punctuation. And our interest in the maps of desert towns probably stemmed from the fact that they seemed like the articulations of territories apparently without content. But although a love of the desert is one of our deep motivations, in this particular case we felt more concerned with a type of codification than with any object of representation. It was in an intuitive way that we set about painting pages taken from maps.

Looking back, the main thing about these paintings was that they replaced an iconic mode of represent-ation by a system of codification which was more like that of a language.

“Painting together”: it’s an expression that suggests something of a paradox, I feel. The act of painting, at least in the modern world, is generally associated with a more or less creative individual. So how do two people paint together? What’s the process like? In concrete terms, what were the procedures that you worked out?

At the start, we thought about projecting the maps onto canvas, and then painting them. But it didn’t come to anything; and we also saw it as a somewhat dated technique. So we started laying out the paintings on trestles, and working with rolls of adhesive paper.

In our catalogue Séries Américaines, we talk about the implications of this “flattening-out” operation: “In the production of our paintings, we take into account a certain number of things relating to the grid. These works could perhaps more accurately be described as painting-screens that are not windows ‘behind which’, or frames ‘within which’, but tables ‘upon which’, or coordinate systems ‘underneath which’ images slide, as constituents or traits of a territory. The grid is an ‘above’, a layer of legibility. What passes underneath the grid becomes the field of the painting.”

This discovery of painting was also a discovery about studio activity. It was an unassuming position, which, in the “doing”, left time for reflection, and circumvented the established art circuits.

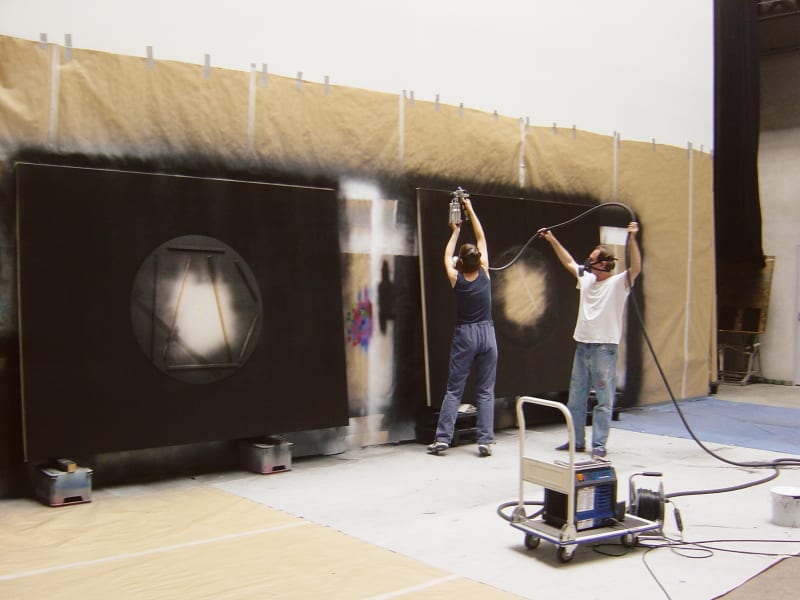

As for “painting together”, there are often four of us: two assistants and ourselves. Before the actual painting can take place, there’s quite a lot of material to be prepared: colours, support systems, masks, wooden structures to keep the stencils at the necessary distance from the canvas…

So you were right there in an activity — painting — with its corollary space, namely that of the studio. If the Séries Américaines, which you’ve just mentioned, allowed you to explore this activity, and this space, this “field of the painting”, what was it that legitimised your installing yourselves inside it? In other words: what were the events that orientated the continuation of your work?

In March 2000 we went to New York. In the apartment we were renting, there was a VCR — of dubious quality, admittedly. But we found a good video store nearby, so we started watching lots of tapes. There was a film by Jim Jarmusch, Fishing With John, about a fishing expedition, with John Lurie and Tom Waits. It put us to sleep [laughs], and when we woke up we found that the electronic snow on the screen was being distorted by the presence of the tape. We were amazed, and enchanted, by the strangeness of the phenomenon. We’d brought along a camera with a biogon lens, and some 6 x 6 positive black-and-white film. Without doing freeze frames, or imposing any choices, we photographed the subjects in movement.

When we got back to Paris, we looked at around a hundred images. Most of them were fine, and we were tempted to make some prints. But in the end, the idea of “television photos” didn’t really interest us: appropriation seemed to have had its day. So we decided to follow the path of information-processing by initiating a painting project.

There’s another paradox here: information-processing through a painting project. I’d like to ask you: “Does it work?” But again: “How does it work?” What procedures did you adopt in the Tapes series?

The term “tape” refers both to the video tape that generated the image and the adhesive rolls we used in making our stencils. Between these two stages, there was an information-processing operation which, for us, was decisive from the pictorial point of view. The photographs were firstly digitalised and transferred to an image program. Then they were vectorised and processed using a graphics program that was compatible with a cutting machine which could produce stencils on the same scale as the paintings.

So at this point we’d turned an image defined by pixels into a vectorial drawing represented by Bézier curves — which allowed us to make a motif as large as we wanted without any loss of definition.

We were interested both in the starts and the ends of video tapes. We deliberately stood on the margins of the image. Our initial idea was to use full-screen images in the course of formation and deformation. The Scratches are accidents taken from the leaders of tapes.

These accidents, which were visible on the screen, were represented in such a way as to signify the scanning of the electrons: they were painted in blanks, and then, with a slight shift, in white acrylic highlights. The background of the screen, normally black, was painted brown, like the colour of magnetic tape. In bringing together the image such as we saw it on the screen and the materiality of the tape, we wanted to introduce a new perspective into our work.

In the Snows, where there’s no signal, the electronic snow’s altered by the passage of the tape.

We gave the image four layers — two in grey tones, one in black and one in white. The result was a sort of millefeuille. Placing ourselves “short of” the image (“less than an image”), we dissociated the layers, some of which we kept. We didn’t try to reproduce an image, but stayed on one side or the other.

Since then our project has opened up considerably. We realised that these paintings had a link with our previous paintings of maps. In both cases there was a iconic field that was defined, not by a limited area but by its passage beneath the cartogra-pher’s grid or across the computer screen. This brought us into the interior of some “snows”, not only in the direction of the passage but also that of the screen loupe.

Working within the fragment, we abandoned the homothesis and orientation of the screen. The forms we were discovering, detached from their referents, were difficult to identify — falsely familiar.

Chance came into your discovery of televisual “incidents”. And it was also, presumably, associated with your “visits” to the middle of the screen loupe. What part did decision-making play? In the field that moved past, what caught your eye? Would you talk about “aesthetic decisions”?

The motifs that interest us, essentially, are the most aggressive ones. Like many other artists of our generation, we were influenced by minimalism. Our raw material provided us with forms we couldn’t have invented or imagined: floral, baroque, extravagant forms…

As we went further into the screen loupe, we found more and more interesting things that didn’t really suit us; and on the other hand there were gradations, ornamentations, decorations, canonic forms that seemed to refer in a tangential way to the history of painting.

The image that spontaneously came to our minds to describe our paintings was that of fishing — a catch in a limitless ocean, either at the surface or in the depths. What we found was always unique, whether or not it belonged to a known family. As we went deeper, the forms became simpler, more elementary, more unexpected.

In Edges, on the contrary, we enormously enlarged segments or straight lines on the periphery of the electronic snow, which finally turned out to be complex sets of incongruous, discontinuous motifs, arabesques and swirls.

So it’s not by thinking about form that we create new forms, but by inventing new conditions for their emergence.

How do these painted images differ from others whose subject comes into being, in a sense, during the production process itself?

The difference lies in the fact that they’re born out of a generative system. Their forms are engendered by the way the information’s processed. They seem to come from elsewhere. If you look closely at them, you can see that some details would certainly have been simplified, or even eliminated, if they hadn’t been reproduced by the cutting machine. We certainly didn’t want to obliterate these details. It was a matter of principle — we see them as a central feature of our painting.Another important point is that we work in curved space. It’s a discreet presence, but in Fishing With John #21 to #25 you can see an after-image of the curved screen.

As Thierry de Duve observes in his 1980 essay Ryman Irreproductible, it was only in the 1960s that a type of painting “after photography” emerged, integrating the photographic function into painting. Could one go a step further and say that you, in turn, are doing painting “after television”?

We generally start out with negative protocols, excluding the pictorial problematics of recent decades, even if they interest us. We don’t want to talk about the materiality of the work, the way it’s made, its texture — or the gesture. It’s true that we wouldn’t claim we never do any “prettifying”. But that’s not the real point. Our criteria are mostly subjective. These paintings have changed our taste and transformed our perception.

We’re often criticised for making pictures to be hung on walls in a traditional way.

In fact the problem of the painting, in its relationship with space, doesn’t really concern us. Our intention is to position ourselves beyond the history of its alienation. We don’t hesitate to reformulate the question of painting by changing viewpoints. And in the same way, we’re sometimes accused of painting abstract figures, whereas in fact we produce “figurating” figures.

Our paintings talk about the image — its emergence, its formation, in its setting, the “all around”. It’s the disparity, the distance between a painting and its referent that seems important to us. On this point, right from the start, we ruled out the idea of talking about the image through photography, so as to avoid any ambiguity or reduction. The history of painting introduces, de facto, a “beyond” the image.

You’re investigating the “unconscious” of the image. This isn’t visible on the screen, but it’s there in the TV tube. Have your methods changed, in the same way that audio-visual technologies have done?

In 2001, we started getting interested in the moment when a TV’s switched off; when the image gets condensed into a point of light.

Having tried in vain to photograph these instants [laughs], we bought a digital video camera. With the Switches, we moved over to colour. No tape this time, just a TV set. What interested us was the moment when the image flipped over towards light; when there was a memory, a residual image on the screen.

So you went back to the US… Did this trip come through in the project?

It’s true that travel’s an integral part of our work. And the Switches, like the paintings of maps and the landscape neons, are tied up with the American desert. We spent a month going from motel to motel, collecting TV switchings-off. The names of the towns we stayed in provided the titles of the works, and each sequence was based on a particular TV set, the station it was tuned to, and the final image.

Night-time accompanies these encounters of the third kind in the motels where you stayed. Isn’t there something a bit theatrical, or ritualised, in your way of presenting your work?

We worked in darkness. We used an ironing table and an ice bucket as a stand for the camera, and a small matchbox as a wedge. Then we start recording. Stretched out on the bed, we switched on the TV, then switched it off again. On-off, on-off, in hour-long sessions — this was our travel ritual. It was only when we got back to Paris that we carried out a close examination of the tapes. The sequences were classified in the form of “contact prints”, image by image, and the ones we selected were then analysed using the same software as for the Tapes.

The ones you selected often seem to have come from the end of a switching-off.

Those were the ones that got closest to light. With the compression of the image, the colours became more elementary, more primary: RGB (red, green, blue) — those of the cathode ray tube.

You did everything yourselves, from the TV you filmed and the processing of the image to the finished painting. From motel to studio. One might talk about “house painting”, by reference to “house music”. The work’s not delegated, though of course it’s not all done by hand either — sophisticated technologies are used.

The idea of “house painting” suits us very well. Whether travelling or at home, this is a kind of housework — that of a couple — and our ideas are drawn from the surrounding world. Also, we’re looking for greater autonomy, and this has given rise to more advanced studio work, as far away as possible from the latent pressures that permeate the world of art, commerce and commissions.

The idea of a “golden age” of painting — that of Titian or Rembrandt — is indissociably linked to working in studios. But the studios in question had large numbers of practitioners occupying hierarchical roles. To me, your kind of studio practice seems a bit different, and I revert to the notion of “painting together”, even if you sometimes have assistants. In your pictorial studio work, there’s a physical input that’s not associated with other, more passive occupations such as watching a TV set or a computer screen, which are aimed at users of one kind or another.

What we bring back from our travels are maps and television images, which are also forms of information-processing. In the case of television — where the information arrives in every household on a daily basis — the emitted light conveys images from around the world, with their complement of judgements and ideologies. We prefer to explore what’s situated on the margins, in the “dustbin” of the image. We find real freedom there, for ourselves and for our work. The reason why we want to preserve as much autonomy as possible is not because we want to avoid faulty work — or at least it’s not only that. The point about the studio is shared time. As we progress in our work, it takes on a sense that often diverges from the initial project, and contains the seeds of further developments. If we had to out-source everything, the work would probably stagnate within the confines of the initial project.

How many pictures did you feel were necessary to really understand this project, and take it to its limits?

We did around sixty Tapes, and almost thirty Switches.

There have been other changes, too. At a certain point, you “switched” from a black to a white background…

In the Switches, the backgrounds are mostly black. One day, during the analysis of Alpine, TX #560-1, a “bug” dissociated the background from the figure.

But the background turned out to contain information that had never previously shown up — a plethora of small, curiously-shaped confetti. We decided to paint these figures red on a white background, in order to emphasise the error and eliminate the background. Which was how Alpine, TX #560-2 came about.

We then decided to paint other white backgrounds, even in the absence of information, so as to bring out this absence. During the same period, we started using a different method for making our stencils — not with adhesive rolls, but with sheets of acetate placed at a predetermined distance from the canvas. The resulting fuzziness was better at rendering the vibration of the light, thus allocating time to the image. As regards our recent paintings (Leblanc #4.1, and Leblanc #9.1 to #9.3), we’ve tried to give the background back to the background (so to speak).

When we filmed TV sets, we focussed on the texture of the screen so as to bring the background up to the level of the figure. The emergence of the background entailed the dispersal of the figure.

You proceed like painters, from a “something seen” to a “colouring sensation”. Is this an allusion to Cézanne?

There’s always a reference to Cézanne in our work, and especially in the Switches. When we painted our first TV switching-off, Alpine, TX #193-1, in 2002, we were thinking of Cézanne’s apple — not just its shape, but also its mode of execution.

When we work with adhesives, by masking, the paintings are mounted in fragments, detail by detail, and the full vision’s only revealed at the end of the execution… In a letter to his mother, Emile Bernard reported that Cézanne worked “detail by detail, finishing the parts before looking at the whole”.

Does your work indicate a way in which painting could get from technical procedures to questions of perception?

In terms of perceived colour, the specificity — the difficulty and the impossibility — of our work on colour has to do with the fact that we transcribe light into painting, moving from an additive mixture to a substractive mixture; which is what gives our paintings their distinctive colours. We always go from red-green-blue to cyan-magenta-yellow-black, then we print a colour chart that we reproduce as faithfully as possible in acrylics.

If you watched TV on a computer, it wouldn’t work…

No!

You’re good “Cathodics”…

[Laughs] Right! But let’s make it clear that our work combines a moribund technology with computer software. And it’s the same thing for our cutting machine — the kind that signwriters use — which has allowed us to produce many complex figures.

So are you reinventing painting by using techniques from the past?

You could say that! But we also improvise. For example, we make the wooden frames that are needed to keep the stencils at the right distance from the canvas.

Does your studio work have a limit, or a term?

We’re currently thinking about the coding and decoding of images. It’s a real contemporary issue — an economic issue. And the idea isn’t only to transport images, but also to control time, to redistribute iotas of time via fibre optics or satellite. We asked one of our collector friends to find out what the engineers at Thomson had in the pipeline, and what was going on beyond the 0s and the 1s — what could be seen in the flow of raw data. After creating an interface, they gave us a six-minute Mpeg video cassette of these unrefined, animated, pre-decoded images.

Since then, we’ve been doing new paintings — the Flows, Glitches and Metablocks — which show the block transformation of images generated in the flows. And we’ve done multiples of these flows.

Couldn’t it be said that artists render visible what people don’t really want to see? You’re in the world of art, not the world of science…

In the same way that it might seem absurd to do multiples of paintings, the fact of showing raw data circulating round optic fibres might seem futile. Art is what interests us. It’s a space that’s distant from the world; a critical space of many transient possibilities.

Looking at your photo albums and videos, you obviously choose just one in a thousand. So a thousand images end up in a single painting. People don’t dwell on a painting the way they look at an image.

We often say that our paintings speak of images, and that our photographs speak of painting, which gives the image a certain time for reflection, not to be “just an image”. It gives it another status. And this is probably why we also take photos of the sky; because you have to contemplate the sky. In which case it’s the sky you’re looking at, not the photograph; whereas with paintings, what you’re looking at is the painting beyond the image.

Whether in the suprematist fourth dimension or in the clouds of the classical perspective, there’s always a relationship between the theorists of vision and its exponents — between the analysts and the painters — as Hubert Damisch demonstrated in L’Origine de la perspective.

Between disciplines, there’s always a contemporaneity effect. Our representation of the world’s always contemporary. But we also try to swim against the current. So our photographs express painting, and the monochrome. They’re an illusory attempt to create an ideal image — of the order of ideas. In the digital age, and in a reactive way (though it’s a bit late for that), they attempt to push back the limits of the silver-based. And then there’s a protocol that’s not negative: cloudless blue sky, a non-polluted urban environment, frontality, precision of aim, absence of manipulation. Les Ciels place their own failure in the balance.

And painting… Why are you attached to a medium that’s currently regarded as retrograde? Why a “return to painting”?

We haven’t returned to painting. In any case you never return anywhere, because everything’s shifting. It’s already different by the time you get there. But there’s always a residue, a trace, which survives, and resists — it’s a “survival” in the Warburgian sense. And Georges Didi-Huberman’s L’Image survivante was present in our minds throughout the execution of the TV-screen paintings — in fact we bought two copies of the book so that we could read it together, and at the same pace. Even if there was nothing left except television, we’d like to think that, using electronic snow (the absence of any signal), or the switching-off of a TV set, one could reconstitute the entire history of the forms invented by humanity — dislocated, displaced, scarcely transformed, deformed. We envisage a history that’s neither linear nor continuous, nor even cyclical, but rather situated at a crossover-point of worlds, cultures, journeys, readings. From the journey to the sedentary studio practice, our relationship to art is primarily that of a life project. And there are other series to come, in which we’ll re-examine the question of territory by integrating ourselves into the landscape of our paintings.

September 2004

Translated by John Doherty